Darr’s Mountain Shop was three stories high and sided with rock. The gneiss blocks sat a bit proud of their mortar making for a good climb to change the light bulbs up under the eaves that illuminated Darr’s Mountain Shop. Everett Darr had been, in his day, a solid performer on rock, snow, and ice. He feigned disinterest or annoyance at my buildering solos, but there was a twinkle in the old man’s eye.

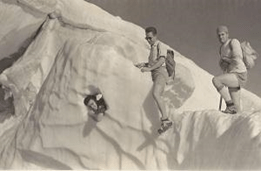

On Mt Hood’s Eliot Glacier: (R-L) Darr, Mount, and Calkin, 1930s. (Photograph courtesy of Gary Randall Photography.)

By then, this early spring of 1978, all that remained for Everett of climbing and skiing were remembrance and tall tales. Bone breaking falls and old age had made his joints arthritic, his walk a shuffle. Nothing, however, had diminished his spirit.

Tough as an old boot is a cliché, but Darr was; he would give a man nothing that was not earned, neither wages nor respect. Some disliked his gruff manner; others accepted him as he was. Some thought his stories a bit too tall, but the man’s record speaks for itself.

Washington’s North Cascades saw Everett and wife, Ida, make numerous pioneering efforts on peaks that were, in the 1930s, all but inaccessible . Mt Hood, on the other hand, was in his backyard. Darr, with Jim Mount, put up a first ascent of what became the Wy’East Route on Mt Hood. In 1940, he added another first ascent, this time of St Peter’s Dome in the Columbia River Gorge again with Ida, Joe Leuthold, and Jim Mount.

But those days were gone now. Only the memories endured.

Down in the basement of the Mountain Shop where the rental skis were kept, time passed slowly on rainy winter afternoons. Everett would always stop by and tell a tale. He never mentioned his triumphs, only the hard times. The grey skies reminded him of a night in the North Cascades after an attempt on Mt Goode. He and Leuthold were caught out by darkness, wind, and rain. They crouched in a tree well with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Leuthold rummaged in his pack. Extracted a bottle of whiskey. They drank to their two left feet and cowardly retreat.

Another day in early spring on Mt Hood: weather coming down with the darkness. He, Ida, and Joe, skiing this time out, came to a steep pitch laden with snow—it might have been Newton Clark glacier, or Eliot, or Coe. Everett did not always have the names quite right; but if all the facts were not straight, that was just too bad. The listener always knew he had been there, and usually before anybody else.

That steep pitch they faced had stopped them. Below, the crevasses had begun to gape open. A fall would be a dangerous occupation. They had traveled light, as usual, and a bivouac was not an option. Leuthold did have a length of rope. He offered a belay. Everett gallantly deferred to the lady. Ida roped up, poled off gingerly, turned slightly downhill for a bit of speed and just then a slab cracked and sloughed off beneath her. Down she went, flailing to stay on the surface of the slide.The rope went taut, and held. The avalanche rumbled off down the mountain. Everett hooted to salute his wife’s survival and skied quickly across the firm slide path.

One storm bound day in the basement of the shop—the snow had just slid off the roof three stories overhead and had effectively destroyed a Volkswagen parked too near the building—Everett leaned against the mounting bench and regaled me with an account of storm climbing. The middle of January had finally delivered some nasty weather. He and the usual suspects spent the night in the old Timberline cabin on the Palmer snowfield. By dawn they were off. Through wind driven snow they plugged up the snowfield.

Reaching what they determined to be the Triangular Moraine, a pow-wow was called. Conditions were, well, marginal. Wet and cold, they decided to climb on. Through the morning hours, the winds subsided, the snowfall became intermittent. Someone suggested they have some lunch and wait for the weather to worsen.

But up they went. As the day waned, the storm returned with a vengeance. Voices were lost in the wind and snow. They communicated with tugs of the rope. As Darr—or Calkins or Mount or Leuthold—crested the Hogsback, the wind tore at him. Up he went, a sack of bones and flesh in flight, picked up and tossed in a bundle down slope.

They huddled together. Great sport, they all agreed; but the day was gone, so down they went. Darkness had caught them, but it didn’t matter. They had not been able to see anything for hours anyway. Skill or luck or just plain orneriness saw them back to the cabin.

Looking north from Leuthold’s Couloir, photograph by the author, December 1981, with the Columbia River beneath the line of cloud and, in the background, Mt St Helens and Mt Adams.

One dismal spring day with rain and sleet, I waited as I heard Everett coming down the stairs, one step at a time. It took awhile. He stopped at the bottom of the stairs and looked around the corner into the shop. Outside, ravens commenced squawking.

“You got my hat?” Everett says to me.

“No, Everett,” I say. “I surely don’t.”

“Why not,” he snaps

I raise my eyebrows.

Everett shakes his head, puts on a sour face. He looked back up that long flight of stairs. He had remembered where his hat was.

Suddenly, he grinned, an elfish smile. “Damn steep stairs, ” he says. “How about roping me up? Awful steep. How about a belay?”

And then he turned, took a good hold on the rail, and up he went, one step at a time, up he went.