Begin with a ubiquitous story of tea: The professor visited the master to test his understanding of zen. The Master offered tea. As the tea steeped, cups were placed. The professor went on explaining his visit, explaining zen, explaining Buddhism and its import in Japanese life. The master lifted the pot and leaned to pour tea for the professor. As the cup filled, the professor became quiet. As tea began to run over the table and onto the tatami, the professor could no longer contain himself. Stop, he cried. Stop, it’s full, it’s full. The master withdrew the pot, setting it carefully onto a trivet. Just so, he said.

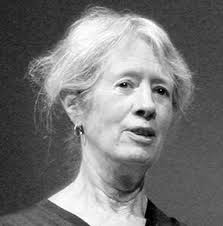

Lyn Hejinian (1941 – 2024)

The brain of a human contains 86 billion nerve cells. Unlike a tin pail filled with water, sensations, perceptions, conceptions will never ‘fill’ the brain. Consider the man, like the professor, who is full of himself. The metaphor describes a person who has an exaggerated notion of self worth. Egocentricity is his stock and trade.

Empty headed is another metaphor used to indicate a person who does not think before he acts and so often behaves impulsively and mistakenly. The metaphor often suggests an unintelligent person, though behavior is not necessarily related to intelligence.

Many 19th century psychologists subscribed to Sherlock Holmes’ notion that the brain was a vessel whose volume was finite so best not to clutter it with nonsense.

The cup of tea suggests the metaphor rather than the physical fact; and the professor might be described as empty headed despite his discourse.

The master might also smile at the notion described above of empty headed. He would no doubt say that an empty head is just the thing. One cannot add to a full head. The metaphor has morphed from an impulsive person who acts without thinking to an intuitive person who acts without thinking.

Consider poetry. E. E. Cummings, perhaps, a good place to start, a poem titled Since feeling is First:

since feeling is first both

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the world

my blood approves,

and kisses are a better fate

than wisdom

lady i swear by all flowers. Don’t cry

– the best gesture of my brain is less than

your eyelids’ flutter which says

we are for each other; then

laugh, leaning back in my arms

for life’s not a paragraph

And death i think is no parenthesis

This is not, obviously, a Shakespearian sonnet. This is:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Consider: The dog ate the car. Though syntax and grammar are correct, diction has led us astray. Though understandable, the words make no sense. The reader might even feel somewhat used: the brain reads ‘cat,’ does a double take and so reads ‘car.’

If we write: the dog eating the car left spilt milk on the kitchen stool pigeons flying overhead; and then change the shape of the line to:

the dog eating the car

left spilt milk on the

tumbled stool

pigeons flying overhead

What results is jumbled syntax and an open ended poem (of sorts) that invites (or perhaps repels) the reader into the process rather than closing him or her, as the case may be, out (slam).

Shakespeare’s sonnet does not invite comment about form or grammar or syntax or diction. One may reflect, but the poem is a closed book.

Poet, essayist, and educator Lyn Hejinian became the leading figure of the Language poetry movement of the 1970s which supported experimental and avant-garde poetics. She became more concerned with the specific issue of openess in both language and life after the death of her daughter-in-law at a young age. She rejected the notion of closure and thought that inclusion and acceptance (the open hand) were imperative to facing both the travails of daily life and writing words.

In her essay ‘The Rejection of Closure,’ she writes: The ‘open text’ is open to the world and particularly to the reader. It invites participation, rejects the authority of the writer over the reader and thus, by analogy, the authority implicit in other (social, economic, cultural) hierarchies.

The open hand and the empty head are not two things.