a short story from CONVERSATIONS WITH A HYPOXIC DOG (A review is coming soon to BOOKS)

The clutter of the office made her uneasy. She wished to straighten and dust. The books were all in disarray. He had forbidden her to touch anything. This wasn’t the house, though live here he did. His life at the university. She rarely visited the place.

He had pushed books and papers aside to open the slender volume of black and white photographs. Simple it was; yet elegant. Just as the photographs were. He had decided at last to bring them hom

“They don’t say anything,” she said.

“Listen harder.”

“O cute. There’s no context here. Just pictures.”

“Photographs. Context all inclusive.”

“What? Like paintings?”

“Yes.”

“Abstracts, smear of paint and an onion skin. That sort of thing?”

“Yes.”

“They don’t say anything either. The nudes like the morgue on TV. They make me shiver.”

“Corpses?”

“Look at this one.”

They looked. The silence grew slowly palpable. She fidgeted at the buttons of her blouse. Her frazzled auburn hair framed a pale face, green eyes. An image of some prepubescent fat girl surreptitiously picking at her wedged underwear made him smile. He shifted his weight away from her. His hands found the pockets of his coat.

“Is it erotic? Do you think? Men see things different.”

She over bit her bottom lip and tilted her head towards him. Her hand touched his arm.

“She’s a little fat. Do I look like that? What do you think? Is she sexy?”

“Umm. If you want it to be.”

“That’s no answer.”

“Well, it’s not about sex. Not in the conventional sense.”

“Everything’s about sex. Or money. So nudes sell. Western makes money. That it?”

“Weston.”

“Whatever.”

“No.”

“No what?”

“It’s not about money.”

“I give up. What is it about?”

“Who’s on first.”

“What?”

“Nope. He’s on second.”

“Who’s on second?”

“Nope. Who’s on first.”

“Well, who is?”

“Exactly.”

He was laughing then and shaking his head. She turned to face him, and slapped him open handed on the shoulder.

“Aren’t we the superior one.”

“Come on, let’s get coffee. I’ll tell you a story about a dead squirrel.”

Past the window of Martinotti’s pedestrians passed looking in, the quick glance, looking away. He had waved to Jimmy as they entered and held up two fingers. They sat at a small square oak table near the front window amidst the clutter of the old delicatessen. The disarray provided ample distraction, and he always felt somehow invisible beside the wine crates and cheeses, the shelves of pasta, hanging garlic, odd groups of dishware, pots and pans, mishmash of tables, chairs and benches each with its newspaper, magazine or book, and the erratic hum and rumble of the heavy old coolers along the back wall.

“The place hasn’t changed much.” She had not been there since the summer. “Your classroom.” The woman sat and looked. He had taken the chair facing the window. “That girl was here with the others. What was her name? You told me once.”

“Celia,” he said.

“Celia. Odd name. I don’t like it much.”

Sunday morning. Gray skies. Drizzle. An old couple, each with salt and pepper hair, his in a pony tail, hers free down her back, sat at a round wooden table painted bright red. Their chairs were green. They sat together and sipped espresso from white demitasses. Animated conversation draped them with a confessional anonymity. He leaned in to her; he spoke; they laughed out loud together.

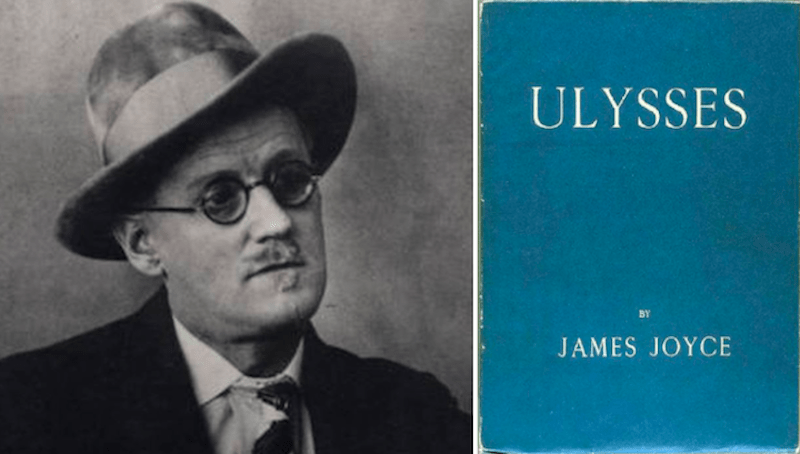

Envy turned him away from them. Many of the pedestrians walked past hooded and huddled. Young faces. Many students in this district. Old buildings. There the Hotel Joyce. The rooms above the fish house. Rent by the hour, the day. Who would stay there longer? No one went to the Hotel Joyce for the view.

Jimmy arrived with their espresso. “How goes the war, my Professor?” he said, a hand deliberately placed on the man’s shoulder. A nod to the woman. “Mrs. Professor,” he said.

“No doubt we are overrun,” said the man.

“We are forced to live in our heads.”

The man nodding. “E il Patrone? How is your father, Jimmy?”

Jimmy put a hand to his ear and fingered the studded lobe. “Without Mama …” He shrugged.

“My condolences.”

Another touch of the shoulder. “Enjoy.”

The woman watched him walk away. She said, “How do you tolerate that queer?”

They sat in silence. She looked out the window. The old couple at the red table spoke now in Italian. The man had lit a cigar; a rich and redolent odor diffused. He then had suggested that the size of his cigar was not equal to the business proposed. The woman had murmured her response, and the old man had snorted his laughter.

Sipping the last of his coffee, he considered his wife.

Still turned away, she said, “So what has this Celia to do with a dead squirrel?”

“More coffee?”

“Tell me the story.”

“All right.”

They had come from the art museum. His student. His friend. A brilliant young woman. He was perhaps bewitched. Something in her left profile, an elegant line, and the delft blue of her eyes. Self-contained, yet mischievous. A boon companion never far from laughter. Yet her silences begged questions.

Teacher, student.

But student, teacher as well.

Of late, it seemed, both students.

And, of course, both teachers too.

From the museum that day they had come upon the Hotel Joyce. The allusion became in a moment the antidote for his illusions. He gave in gladly to tomfoolery.

Celia had said, “You wouldn’t dare.”

He had taken her by the hand and quickly through the door of the Hotel Joyce. The officious clerk looked on as bland as he was blank. Clean-shaven, younger than he should be, well spoken. Sitting on a stool behind a glass cage in a narrow, unkempt lobby.

“Good afternoon,” he said. “May I help you?”

Student leaps into hesitancy of Teacher’s sudden discomfiture.

Celia said, “My uncle and I need a room for the afternoon.”

Up the stairwell, co-conspirators, the laughter bursting from them. The key in the lock. After you, Gaston. But no, I insist. To a shabby disappointment. Smells dominated. Disinfectant. Mold. Cigarettes smoldering. The view of window and brick. Better to pull the shade. They sat somberly on the bed and inventoried the furnishings.

Threadbare carpet. Grayish. Frazzled. Stained. Clearly beyond redemption. Celia insisted on blood stained. Melodramatic, he replied. Frankie and Johnny, she said.

A nightstand thickly painted something brownish over greenish over sortawhitish. The color of sewage.

A lamp. The shade appeared to have a bite out of its lower end. They could not agree on this.

A chair. Against the far wall. But not so far in this small, narrow room. The chair painted to match the nightstand.

A painting, above the chair. Of flowers. Cut, arranged by chance in a vase of brilliant blue.

Off white walls. Water stained in that outside corner. Patched and not textured there on the hallway wall.

“Nice vase,” he said.

A shrug and tilt of head from her. Perhaps a smile.

They sat together on the bed and bounced to hear the springs creak and groan. They sat still.

“We’re not seeing what’s here,” Celia said.

“Not seeing a bathroom. Probably down the hall. European model.”

“No, listen. We’re making judgments. We’re abstracting the room.”

She sat to his right looking at the chair, the painting, the window. She studied the bare threads.

“Do you remember the squirrels,” she asked.

He smiled. “Oh yes,” he said. Student takes teacher for a roller coaster ride, he thought.

“We were talking about love,” she said.

“We were on a run. We had broached a concept. I plead hypoxia.”

She hadn’t heard. “No, I had asked you about …”

“Medicating neuroses,” he said into her reluctance.

Her head nodded assent.

“Depression, for example,” he said.

She sat still.

He said to her, “A last resort, we agreed.”

“And you talked about simply waiting with the certain knowledge that things would change. Today it is raining. Tomorrow the sun shines. Yes? Something like?”

Springs squeaked, nearly a drunk’s hiccup, as she turned to him.

“Yes,” he said. “And then I boldly went on to suggest that love was an able antidote as well. Or could be. It requires mutuality.”

“‘Mutuality engenders beatification.’ Your phrase.”

Laughing. “Quiz on Tuesday,” he said.

“But we left love sort of … hanging?”

“Yes.”

“Who’s on first.”

“Yes. Perhaps that kind of ambiguity.”

“About love?”

“Yes.”

She looked past him out the window. “And then the two squirrels darted across the road in front of that van.”

He stood up and paced the room, across and back again. Standing at the window, through the geometry of the buildings a glint of sun from the distant river and just there the gentle arch of the bridge span.

“One ran quickly across,” she said. “The other …”

“Chasing la femme, his heart’s desire. Caught in the maelstrom. Froze and got tumbled end to end.”

“Yes,” she said. “But when the car passed, off again was our friend, the squirrel.”

He turned and grinned. “And as quickly as that, you tumbled my abstraction. You said …”

“‘That’s what love will get you.’” Her arms extended, smiling broadly; her hands turned elegantly up and open. “Ta da.”

Laughing then together. He took her hand and led her foot thumping down the stairwell to wave and grin stupidly at the officious clerk who, bless his soul, tipped a finger from his forehead. Perhaps he smiled.

She had been infectious.

Now the scrape of chairs. The old couple standing at their table. He helped her with the sleeve of her coat. She fixed his collar. A fellow wrapped in a tattered overcoat shuffled past the window. Einstein’s hair. Meaty Irish face.

“But …” She fiddled with her cup, turned the saucer. She centered the salt and pepper. Arranged a napkin. “You said dead squirrel. But the squirrel didn’t die.”

He watched the older couple through the door, watched as they passed before the window and then gone.

“That’s true.”

She waited.

He briefly smiled.

“You’re not saying anything.”

“Not much to say.”

“Well, professor, you are too obtuse today.” A coy smile.

He shrugged.

“You tell me that silly story and now expect me to understand these pictures.” She stared at him.

“Photographs.”

The woman blinked dramatically. Her lips met and then curled slightly in to a nip of teeth, her hands suddenly still.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “That was pedantic.” He put his hands on the table, drummed fingers lightly.

“Pedantic,” she mimicked.

“It’s like explaining a joke.”

“Try me.”

“Fuse the abstract with the concrete and a light illuminates the darkness. There’s more to a stone than hardness.”

“Hardness.”

“It’s what Hemingway did with his stories. It’s what Eliot did with his poetry. It’s what Weston did with his photographs. It’s what Celia had begun to do with hers.”

Her eyes narrowed. “That was her book.”

“Celia? Yes.”

“But it’s … it’s … that’s the one you gave to her.”

“Yes.”

“And she gave it back?”

“Yes.”

She sat back in her chair. Her head nodded slowly. “I remember now. She went off to … to …”

“Italy.”

Suddenly leaning in, she snapped, “You gave her that money.”

He looked back.

She turned away from him and looked out the window. Recrossed her legs.

The painted sign on the building’s back wall for The Hotel Joyce, the fish house below, faded and drab with time.

Angrily back, loudly, “Did you sleep with her too?”

He pushed his chair back abruptly and stood.

“No, don’t,” taking his arm. “I’m sorry. Don’t go.”

They sat in silence. He took their small cups to the counter at the back of the store. Jimmy ran both hands over his head flattening blond spikes.

“Another dose?” Jimmy asked.

“Yes.”

He moved slowly back through the cluttered room. The aroma of the cigar lingered. The faint scent of the woman. Coffee ever present. Dust motes in the window light.

He sat.

She looked to the window and back again. “Espresso,” she said. She looked at the man. “O why can’t you just be football and beer?”

Rain fell.

Tomorrow, sun.