… gonna lay my head on some cold railroad line, let the 2:19 pacify my mind …

Murders have existed since Cain slew Abel, and stories about murders have always attracted eager ears. When stories become songs, ballads result; and a substantial portion of all ballads involve murders. From infanticide to genocide, all variations of man’s inhumanity to man are included; from Scandanavian eddas to African myths, every culture has its demons and demigods.

Most American ballads originated in Ireland, Scotland, or England and were brought to the United States by emigres. They all tell tales of misadventure. The word ‘ballad’ derives from the root word ‘ball’ which is found in both Latin and Greek forms to mean ‘dance.’ (Another form of ‘ball’ gives a spherical object.) The pronunciation of ‘ballad’ and the vagaries of early English spelling created a variety of terms that all came to mean a song sung to tell a story.

Before printing, events of the day were orally reported by the town crier. The more conspicuous of these events became repeated and memorized. After the advent of printing—1440 in Germany—the events of the day were printed on broadsheets and posted. Music became integral to the process both to entertain and to aid memory, and melodies joined with lyrics which enhanced the telling. The songs that resulted were inevitably accompanied by simple instruments such as flutes, drums, banjos, and guitars.

With the advent of printing, the presses began churning out broadsheets, and the ballad was then posted on bulletin boards, doors, walls, and windows. The word ‘ballad,’ also spelled ‘ballet,’ may have gained additional meaning from its alliterative association with ‘bulletin.’ The songs were the headline news of the day, and like headline news stories, most died as soon as they were sung. But the more popular songs were passed on, reinterpreted, and eventually changed to suit some new occurrence.

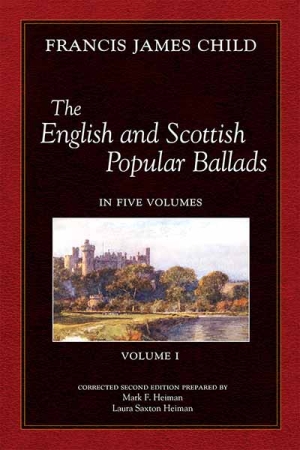

The composers of old ballads, for the most part, remain unknown. In 1860, Francis Child published an eight volume work that included 305 ballads.The melodies and themes have been used time again to create new songs or to give a new slant to the old work. Jealous husbands, unfaithful wives, deceitful lovers taking gun or knife in hand to resolve the unrequited relationship, hard driving boss men, hard hearted bank men, slave drivers, prison wardens, and whip wielding plantation owners all can be found in the stories told by ballads.

Humans have a predilection for gruesome events. From ‘Hunt-A-Killer’ website comes this:

… thousands would flock to these public executions [hangings], and the mood would usually be jovial. With people rushing to get a good spot close to the gallows, these public spectacles were known irreverently as the “hanging fair”, “stretching”, or “collar day.” The events held a carnival-like atmosphere.

Murder ballads from the British isles (Celtic traditions) and their American variants most often find men killing their wives and lovers (‘Tom Dooley,’ ‘Banks of the Ohio,’ and ‘John Lewis.’) Blues, originating in the southeast United States, began as the work songs of slaves, but by the early 20th century, the themes had become centered around women killing (or rejecting) their men (‘Send Me To The ‘Lectric Chair,’ ‘Silver Dagger,’ and ‘Frankie and Johnny’), with the men succumbing to a variety of vices that usually involved drinking, gambling, and fighting.

‘Lily of the West’ provides an example of a murder ballad that became a love song. Originally an Irish ballad, the song tells the tale of a man enchanted by Lily (or Flora or Molly-O depending on the version.) She had other ideas, however, and her new lover paid the price. He was knifed by her jealous suitor. Mark Knopfler, of Dire Straits fame, joined with The Chieftains to record an Irish version of the song. After its arrival in America, ‘Lily of the West’ soon became a standard. A few of the lyrics were changed, ‘Ireland’ replaced with ‘Louisville,’ and the murder, in the American version, often became a matter of self-defense.

As often happened, the same popular melody was used to tell a much different story. ‘Lily Of The West’ became ‘The Lakes of Pontchartrain,’ songwriter unknown but thought to have been written sometime after the civil war. A common practice of all song writers was this business of appropriating melodies, which cannot be copyrighted, and then adding their own lyrics. Bob Dylan, in his early days, did this repeatedly.

The murder ballad (infanticide and a hanging) ‘Mary Hamilton’ might be as old as the 14th century, but the 16th is more likely. While not a story with specific historical precedent, many disparate incidents from various reigns (Russian, French, Scottish, and English) conjoin to make up the song’s lyric.

The king or tsar or prince has his way with one of the queen’s maids, she becomes pregnant, kills the baby by casting it out to sea, and is hanged in due course. Originally known as ‘The Fower Maries,’ dozens of versions have been recorded, the most compelling may be that of Joan Baez on her eponymous debut album of 1960.

Dylan, feeding off the success of the Baez song, ‘borrowed’ the melody and wrote ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’ in 1963. The lyrics tell the story of the murder of Carroll by a wealthy young man named William Zantzinger. Dylan and Columbia Records were threatened with a lawsuit by Zantzinger, but the suit came to nothing. A video available on the internet is that of 22 year old Dylan performing the song after an awkward interview with host Steve Allen.

The folk movement of the 1960s began with the success of the Kingston Trio. These clean cut college boys with the button down shirts recorded ‘Tom Dooley’ in three part harmony, simple instrumentation, and a memorable refrain. While not as topical as Dylan’s account of the murder of Hattie Carroll, Tom Dooley ( or Dula, a Confederate soldier) tells the story of the 1866 murder of Laurie Foster and the subsequent hanging of Dooley. The song went, in short order, to number one on the charts; and folk songs, fusing with blues and rock, became the most popular music genre of that decade.

Historically, most ballads and early blues were performed by single performers with cheap battered instruments. The early balladeers, like modern day buskers, would station themselves on some conspicuous street corner and sing the news. Blues men sang on porches, in town squares, and, when they could get the gigs, in juke joints, smoky dim lit rooms often heated by a barrel burning wood. Inevitably, they would sit on straight backed chairs, sing their songs (often quite a variety) and drink their whiskey. Video of an old blues man named Sam Chatmon (1899 – 1983) provides an example. Chatmon, who played with the Mississippi Sheiks in the 1930s, was 79 years old when the video linked below was recorded by Alan Lomax, John Bishop, and Worth Long at Chatmon’s house in Hollandale, Mississippi.